Stateful stream processing is not a new concept, but some approaches and best practices are still not straightforward and continuously changing. The state itself can be represented in a variety of different ways. I’ve recently spent quite a bit of time learning and building stream processing pipelines that use a particular type of state, and I’d love to share more thoughts on this topic.

Previous State Beliefs

Until recently, I only thought about the state in stream processing in the context of a window. For example, a session window that contains some additional information (perhaps enriched) about the session. Or a fixed window of an hour that contains some aggregations for this period of time. When the window closes, the state is gone. Sounds pretty efficient and straightforward, right? Garbage collection is essential in this case because we don’t want the state to grow uncontrollably (or do we? Will see…).

This usage of state (per key, inside a window) allows us to build great solutions for a variety of problems. Realtime analytics, data enrichment, complex sessionization. Do we really need more?

What Is Global State and Why Is It Essential?

In 2014 Jay Kreps wrote a great article about local random access state in stream processing. The article highlights the requirement of a fast random access state that’s available to stream processing pipelines. He also argues that this state should be local (to avoid network calls when reading/writing to it).

Local or not, the idea of a fast random access state outside of a window seems to be a deal-breaker to me now. Why?

Fast random access state can also be called global state (as in “not in a window”). The idea is extremely simple and powerful: you have a key/value store that’s available inside your streaming pipeline and natively supported by various streaming operators and transforms. Each key in the pipeline has access to its portion of the state. You may choose to store absolutely anything in the state, and it’s not going to be garbage collected (since there is no window close trigger for that) unless you decide to do it explicitly.

The idea of a global, infinite state may sound scary. But it’s only a problem if the state is growing uncontrollably per key, in which case it’s very likely to end up with a skew problem. And if the state is growing with the key space, then we should be fine; it becomes a problem of scaling a stateful system (which can be tricky too). For example, it’s not very different from scaling a Kafka cluster that uses compacted topics. Or from scaling a Cassandra cluster. Or sharded MySQL database, etc. As long as we know the system’s capacity and can linearly increase it by adding more nodes, we can keep growing.

Now, the idea of treating a streaming pipeline as a database may sound wrong, but, again, it’s not that new. And more and more often we hear about streaming and database worlds converging at some point, so treating state in streaming pipelines as something bigger than a scratchpad should not be scary.

Streaming Joins and Global State

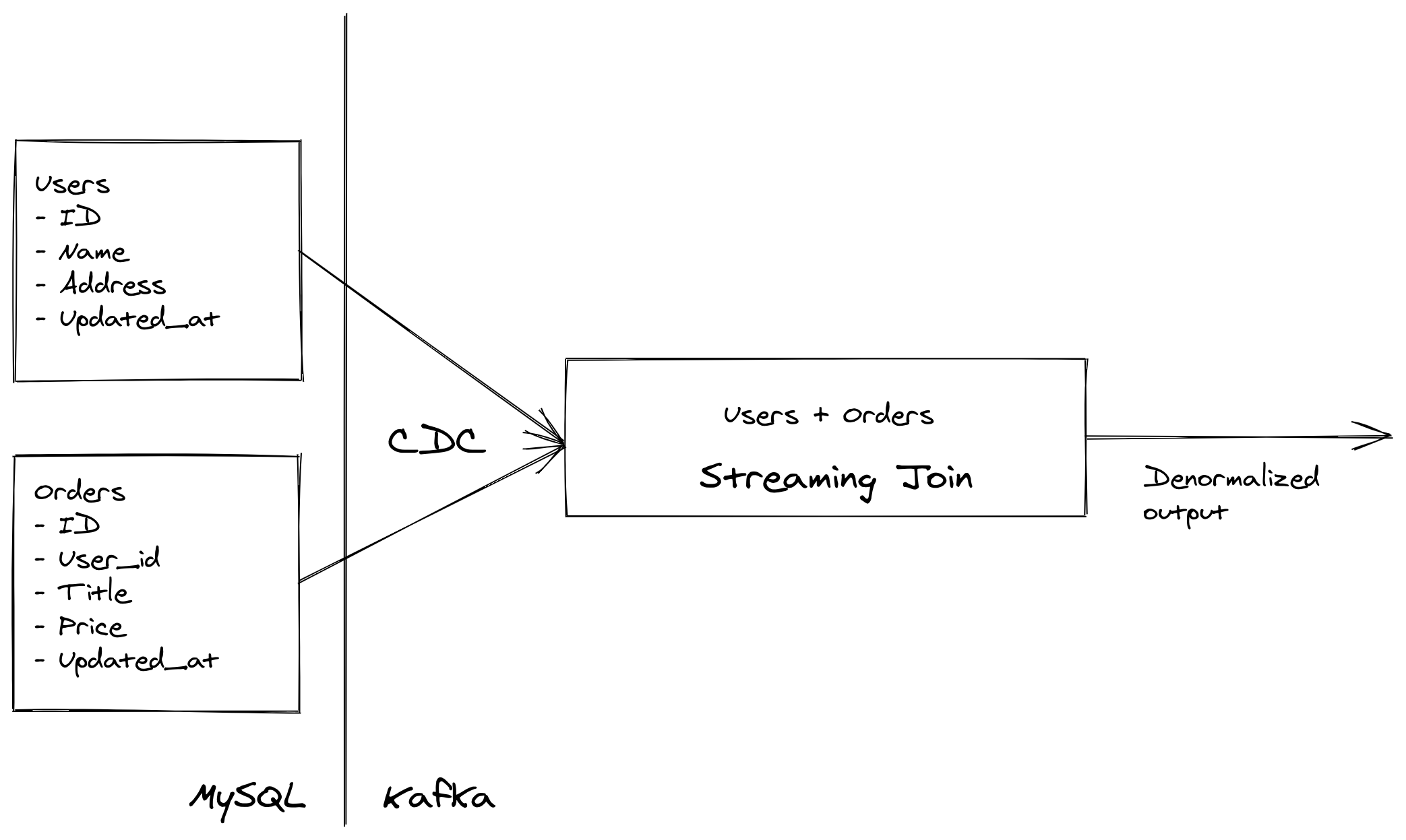

Change Data Capture using a tool like Debezium became an extremely popular way to ingest data from relational databases. This approach’s biggest downside is that it provides highly normalized data streams since it essentially mirrors schemas and relations of normalized tables. In this case, joining these streams is almost necessary: your data model probably requires combining data from multiple streams/tables.

Streaming joins are easy when you can use clearly defined windows with good timestamps - for example, 1-hour window with event timestamps extracted from the message payloads.

There is just one problem with windowing - you rarely know if the interval is good enough. Sometimes you can guarantee that messages will be processed within a window (e.g. when using ingestion timestamp), but usually, you can’t. So you end up guessing and balancing between memory usage and the amount of data you don’t want to drop. Watermarks can help with handling late-arriving data, but unless you have a perfect way to construct them (better than heuristic), they’re not that different from increasing the window size.

And windowing just doesn’t work for these two use-cases:

- When you can’t tolerate data loss, but you also don’t know how late the data can arrive

- When you need to support timestamps that can be very old (e.g. from 5 years ago): you just can’t create a large enough window

These use-cases are not that rare: if you want to mirror all your operational data via CDC into a data pipeline consistently and accurately, you have to implement them.

And global state can be a perfect solution! Your streaming join becomes non-windowed, and you rely on the global per-key state for persisting and constantly updating the result of the join. So, as long as you don’t have hot keys and can scale the state linearly, it’s a very efficient and straightforward way to support the arbitrarily late-arriving data use-case.

Here’s a concrete example:

- We want to join data streams generated by Users and Orders tables (

Orders.User_id = User.ID) - Any row in Users and Orders tables can be updated any time (and

Updated_atis going to reflect it). This is a typical business requirement: historical orders being updated, users changing their names, etc. - The streaming join should be able to emit the denormalized result of the Users and Orders streams

As you can see, it’s impossible to come up with a specific window for this type of join. But using a non-windowed global state solves this elegantly.

Global State Support

Apache Flink provides first-class support for global state via its KeyedStateStore globalState() method. Apache Kafka Streams has a very similar abstraction called KeyValueStore. In both cases, you have a key-value store that supports get and update operations. In both cases, the state can be persisted in a local RocksDB database, so scaling state means scaling RocksDB state store (which can be done vertically by mounting bigger disks or horizontally by adding more workers).

Apache Beam doesn’t natively support global state, but you may get away with global window and state. However, it comes with challenges; global windowing usually has some overhead (based on my experience with Google Dataflow) compared to a global non-windowed state.

Summary

Streaming systems with global state is a powerful combination that unlocks implementation of the most complex pipelines. One of the use-cases that’s very hard to implement without the global state is arbitrarily late-arriving data in streaming joins.

Modern frameworks like Apache Flink and Apache Kafka Streams make it possible to use and scale global state effectively. Also, global state can be a cornerstone for the efficient Kappa architecture, as long as snapshotting and passing state between pipelines is operationally viable.